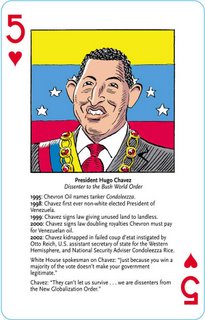

Chavez 4 - Opposition 0

Another day, another victory at the polls for Hugo Chavez. I mean - seriously: three elections and a referendum on his presidency, that's good going by anybody's standards. (Outside your average dictatorship, of course.) This success has been hailed by activists around the world as a victory for the Forces of Light against the Armies of Mordor, but I wonder if they aren't somewhat overstating the case.

Another day, another victory at the polls for Hugo Chavez. I mean - seriously: three elections and a referendum on his presidency, that's good going by anybody's standards. (Outside your average dictatorship, of course.) This success has been hailed by activists around the world as a victory for the Forces of Light against the Armies of Mordor, but I wonder if they aren't somewhat overstating the case.The benefits of the "Bolivarian Revolution" (named after Simon Bolivar, the leader of Latin America's 19th century liberation movement) for Venezuela's poor are undeniable: free medical care; improved access to drinking water; and putative steps towards land reform, to name but a handful. But, as important as these developments are, their significance says as much about the state of Venezuela pre-Chavez than it does about his radicalism.

Chavez's programmes have been predicated to a considerable extent on black gold. Venezuela is the world's fifth largest oil exporter and with the price of oil as high as it is, the economy is surging at an astonishing 9.4%. Sure, the poor haven't done as badly out of this as they might, but its the old elites who continue to thrive:

The economy is surging at 9.4% and banks and credit card companies are reporting exponential increases in deposits and loans. Car sales are expected to more than double this year to 300,000, many of them luxury models, and property price rises rival Manhattan.This is the reality of Chavez's Venezuela: fairly successful social democracy, but hardly a revolution. Douglas Bravo, a former Marxist guerrilla and one-time associate of Chavez averred," If you look at what it has accomplished, it is a neoliberal government."

As Roy Carroll remarked in the Guardian, "property rights and the structure of the economy remain intact, largely because the government does not want to impede its revenue, prompting relief from the elite and grumbles from the radical left who want greater redistribution of resources." In August, the government made noises about expropriating the Caracas Country Club and Valle Arriba golf club to construct houses for the poor. Writing in mid-November, Carroll noted,

Chávismo has not conquered the fairways. The vice-president, Vincente Rangel, scorned the idea and Mr Chávez, not wanting to pick this particular fight in the run-up to an election, said not a word, leaving the mayor to fight a lonely battle against the clubs' lawyers.Although the fight was not yet over, Caracas Country Club president Fernando Zozaya seemed confident the case would be resolved to their satisfaction. "Let's say it's a very special type of socialism."

The foregoing takes nothing from the very real threat to Venezuela posed by US Imperialism, but this is not my concern here. It is possible to oppose US aggression without unquestioningly supporting Chavez. Similarly, one can acknowledge the commendable reforms implemented over the last eight years whilst wishing they'd been taken further and critiquing the elite nature of the so-called revolution, with its troubling focus on Chavez as a putative Glorious Leader. (To say nothing of the people he's made friends with.) Indeed, I'd go so far as to say that such a position is a prerequisite of a genuinely liberatory politics. Vicarious revolution's a lot less exciting than getting out and doing it yourself, anyway.

<< Home